On Emotional Intelligence

7 May 2020

Written by Head of Well-being, Kerry Larby

I have been curious about emotions lately.

My guess is we may be dealing with unfamiliar and mixed emotions. On the one hand, we may feel positivity associated with slowing down and having the opportunity to reconnect with ourselves, our families, and our loved ones. Leading psychology professor, Barbara Fredrickson states positive emotions like love, gratitude and calm allow us to broaden our perspective and make us think and act more creatively and flexibly. They build resilience.

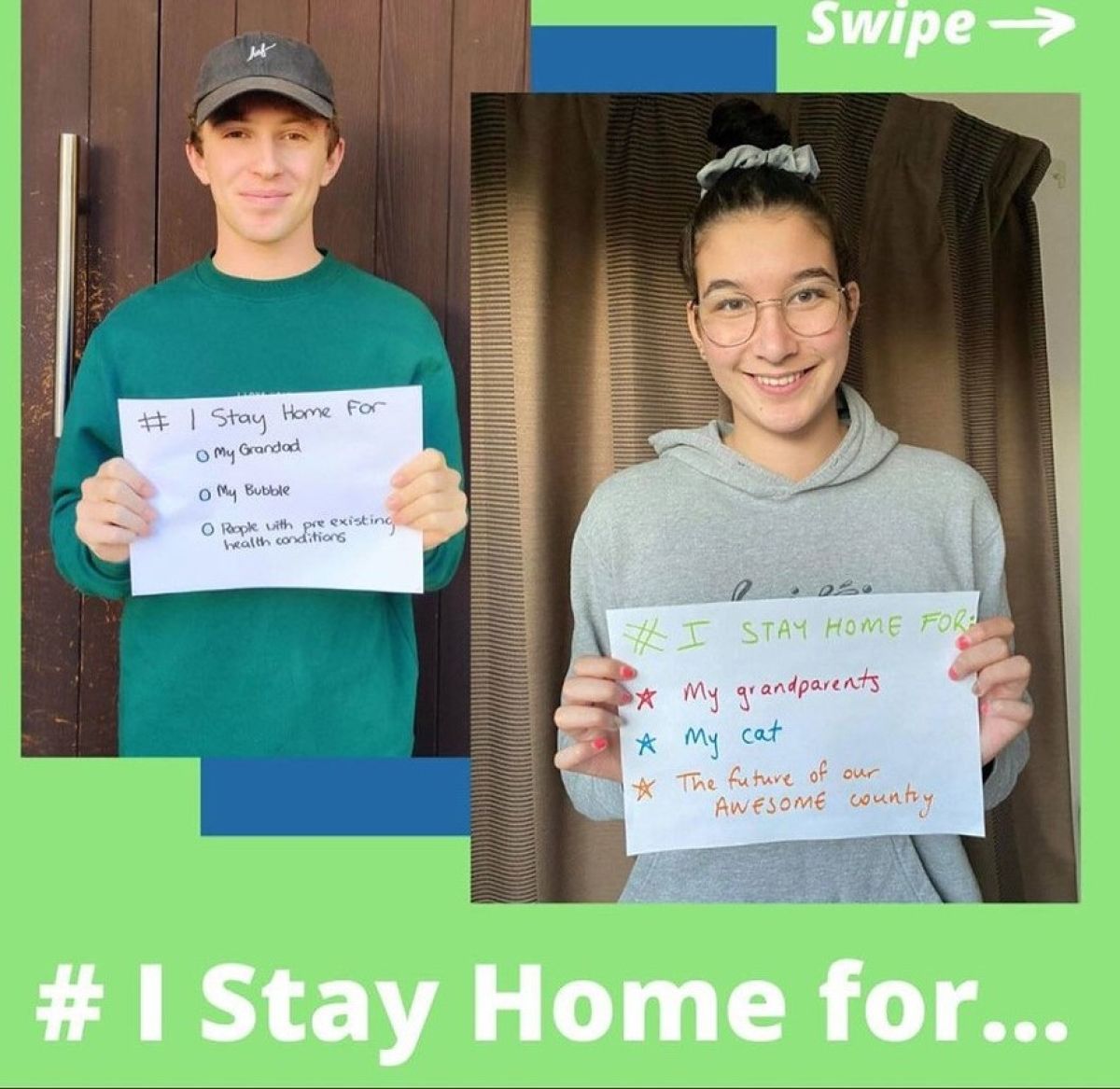

But, at the same time, we are processing a completely different worldview. A lot has changed. With large scale and prolonged uncertainty and upheaval, it is normal for us to expect negative or unfamiliar emotions: loss, disappointment, boredom, worry, and frustration.

Source: The Willows Community School

Accepting the normality of positive AND negative emotions

Last week, I talked to our Head of Guidance, Tom Matthews, about the impact of isolation on adolescent mental health. Mr Matthew's emphasised the importance of families being able to normalise negative emotions and perceived stress. We need to be realistic. Experiencing a wide array of emotions is a normal part of the human experience, especially when living through a global crisis. Says Contemporary philosopher, Alain de Botton, "Let's respect the storm that we are going through and not expect ourselves to be totally sane all the time".

We should not see negative emotions as a sign we are not coping; instead, we should view them as important sources of information. They are cues, signals—telling us to approach or avoid, to stay or to go. Says Professor Marc Brackett, 'It is the range of emotions that we experience—not any specific one, that opens our eyes and encourages us to grow, learn, and become catalysts for change.'

Learning to ride our emotions gracefully requires self-awareness and a set of skills that fall under the umbrella of emotional intelligence. I believe emotional intelligence is the skill that matters far more than anything else for human flourishing.

And without a doubt, it is crucial now.

Emotional intelligence

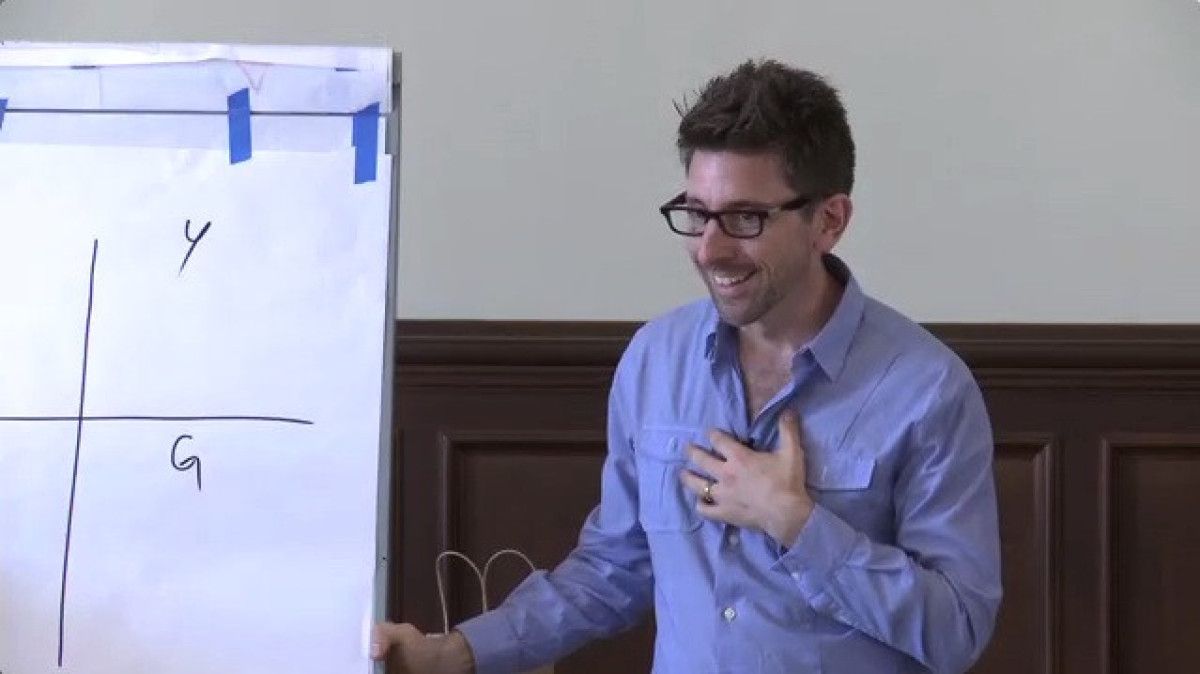

In 2015, I was fortunate to get a scholarship from St Andrew's College, to study with Professor Marc Brackett, the Director of the Yale University Centre for Emotional Intelligence. The course involved learning how to teach the RULER programme of emotional intelligence to students (These learnings have created the foundations for all my understanding of student well-being). At Yale University, RULER is an acronym that explains the components and processes of emotional intelligence. These include:

Recognising emotions in self and others,

Understanding the causes and consequences of emotion,

Labeling emotions accurately,

Expressing emotions appropriately and

Regulating emotions effectively.

It is these skills that will allow our young people to navigate uncertainty in their lives.

So, how do parents and educators teach emotional intelligence to young people?

Permit our young people to feel. This is about creating a family or school culture where it is normal to share and talk about emotions rather than sucking them up or squashing them down. It is about asking, "How are you (really)?" and actively listening. I find it interesting how our emotions are a big part- maybe the biggest part- of what makes us human, yet we don't necessarily talk about them much. Being in isolation gives us this opportunity to experience the benefits of holding space, communicating and being more present with our families. In this podcast, Brené Brown has a heartfelt conversation with Marc Brackett about the importance of giving our young people permission to feel.

Become an emotion scientist. Professor Marc Brackett emphasises the importance of parents and educators becoming emotion scientists, not emotion judges. A scientist is curious, open, and has a growth mindset about emotions. When we are emotion scientists, we actively listen, step back and want to understand the story behind the behaviour. Alain de Botton, refers to this as having charity of interpretation.

An emotion 'judge,' on the other hand, is reactionary, critical and can make quick assumptions with limited information. Unfortunately, judgement can be a natural default in our interactions with others, especially those closest to us.

Develop an emotional vocabulary. Human beings experience a plethora of emotions, yet sadly we have few labels to attach to these feelings. I have noticed a tendency for people to overuse words like happy, anxious and stressed. This can be a problem as a misuse of language has the power to shape how we experience our emotions. Each word opens up a story and the stories we tell ourselves can both influence and undermine our identity. To accurately process and communicate our feelings with others we need to drill down further: Am I feeling anxious or am I nervous? Accurate labeling is important because if we name it, then we can tame it.

Help young people create a toolbox of emotional regulation strategies. Over time, we learn how to regulate our emotions and moods, so we stay on track towards our goals. Whether it be reappraising thoughts, exercising, connecting with friends, connecting with ourselves, being creative, or having a good night's sleep, each of us creates our own toolbox of useful regulation strategies. We can support young people to develop self-awareness by asking thoughtful questions or giving feedback on what we see working well in regards to their emotional lives. We can support them to build their toolbox.

At the beginning of this year, as part of our whole school well-being goal, Dr Sven Hansen shared his expertise on emotion and resilience with all St Andrew’s College staff. We were fortunate to attend an inspiring workshop on how to develop 'situational agility.' Situational agility is about having self-awareness about how we respond to challenging situations- emotionally, cognitively and physically. With Dr Hansen’s tools and framework, we were taught how to be more conscious of our reactions so we can role model resilience to our young people. This learning will be particularly relevant in 2020.

Teach children to empathise. I believe having empathy and understanding other's thoughts and emotions is a deeply important quality for human beings. It is about broadening the perspectives of our young people so they exhibit kindness, humility and compassion and see echoes of themselves in other people. Any conversation that helps young people consider what it would be like to walk in another person's shoes is crucial. Reading fiction and watching films builds empathy too. Our current situation provides a significant context for empathy-building.

Be a role model. Children learn through following the actions of adults around them. Emotional intelligence isn't about being happy and calm all of the time (impossible). Role modeling could mean seeing a parent or teacher acknowledging, expressing, labeling, and processing a negative emotion or situation and then using healthy regulation strategies to bounce forward. Role modeling is about active listening, caring and withholding judgement.

This global crisis will inevitably impact the emotional climate of our young people. Moving forward there are threats and opportunities in regards to mental health. More than ever, we need to focus on cultivating the skills of emotional intelligence in our young people. They matter more than anything.

Related Posts